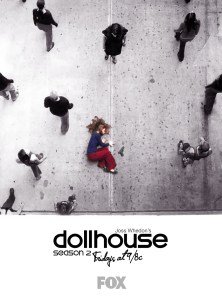

I had many long conversations in this space ten years ago: some with physicists (and one biologist!) on physics and on reading Plato’s Ion, for example. (The “Wily Socrates” thread.) You’ll also find here two posts and some discussion on Shusaku Endo’s great novel Silence, along with a series of posts on the television series Dollhouse; one post on the philosopher and theologian Kevin Hart; and many others on other topics.

Now, in 2019, I’ve prepared a NEW “deepgraceoftheory ” website — it will be at .ORG instead of at .COM — because of all the thinking and studying I’ve been doing since I first tried to talk with natural sciences about topics from Derrida to the early Greek philosophers. I have been thinking about the brilliance of the scientific method, and about the dynamic early-Greek theory of the exquisitely-skilled and highly-evidentiary met-hodoi — those cherished early-Greek “arts of knowing” or “ways of knowing. The Athenian vision of the arts and sciences was cherished also by the successors of Plato and Aristotle, as their understanding of a “philo-sophical” education and way of life spread out and journeyed into so many lands and found a home amidst so many different peoples, cultures, and religions. This philosophical tradition most certainly does NOT belong exclusively to the Western tradition — for some 2000 years it traveled everywhere in the “(then-)known” world, and it was preserved and spread by the rapid expansion of Islam, for example, just as it was by the Roman Christian missionaries to Celtic and Germanic peoples in northwestern Europe. In contrast, however, modern philosophy is assuredly a peculiarly Western phneomenon, and introduced a very different theory of human knowing — modeled on the deductive-apriori of analytical geometry — during the Cartesian revolution in philosophy between 1650 and 1700. As a result, early-modern, high-modern, and post-modern philosophy is its own unique species of philosophy, and as recently as 1979 Paul Feyerabend still had to write his Against Method simply to argue that a natural science is NOT a “philosophy” in the received modern understanding. It is NOT, that is to say, a top-down “system” of “necessary” reasoning. The Greeks and their successors never confused the disciplinary methodoi in this fashion — or identified first philosophy with certainty — a fashion that emerged after 1650 in Western Europe and is so well-described by Ian Hacking in his indispensible books, The Rise of Probability and The taming of Chance. Thinkers schooled like Hacking in British analyti philosophy or like Derrida in the texts of the French Enlightenment are not equipped to read pre-Cartesian texts or perceive the dynamic theory of focused and evidentiary human knowing that is operating everywhere in those texts. But that theory is capable of doing justice to each of the disciplines without setting them against one another. To develop a human(ist) agency within human knowers that respects the exquisite disciplinary discovery-procedures, the discipline-appropriate means of validity-testing, and the scrupulously-qualified truth claims of each of the disciplines was the goal or telos of a “liberating” education, prior to Descartes, and the “freedom” to which it refers is the capacity to think from within a given discipline (with its inherent constraints based on the nature of its to-be-knowns) — and from outside of it at the same time. This kind of tempered and chastened “wisdom” was loved by the earlier and truly liberally-educated philo-sophos, because an agency that knows itself as capable of appreciating and employing the diversity (and even incommensurability) of the disciplinary methodoi will have been innoculated against any kind of tunnel-vision or singleness of mind. And this is precisely the mark of paideia that is encountered in the earlier thinkers and educaters of the arts & sciences tratition. They would not willingly allow any of the disciplinary viae (“pathways”) to trump any of the others — save in respect to its own to-be-knowns. Galileo know this, as did Bellarmine and the other Renaissance Christian humanists, but Descartes in contrast sought to discover a single kind of “Method” that would be universally applicable to every-thing.

This is my offering of thought, in a nutshell, for the consideration and testing of all of the disciplines. Nothing would be more beautiful than to discuss with one another how our disciplinary methodoi work and how they are tested and what kind of validity they claim. But we cannot even BEGIN to do this until we have a richer and more answerable epistemic vocabulary and theoretical framework than what is provided to us by our hopelessly narrow and inadequate, Newtonian-era, theory of knowing: I mean, of course, the “modern epistemo-logy” (or “theory of knowledge”) bequeathed to all of us by the Enlightenment, which was willing to acheived a certain clarity, by banishing all contingent processes from a brand-new kind of human knowing, one outside of time and change: a time-lessly transcendent and transcendental scene of human knowing, modeled on the timeless realm of mathematics” (a timelessness aptly pointed out by particle physicist Lee Smollin, about whose courageous work I have much to say).

The “Wily Socrates” posts constituted my first attempts to convey — to those in the sciences — the early-Greek scene of knowing and its dynamic theory of focused human knowing, the theory (of irreducibly many theories) which launched the Arts & Sciences tradition in the academies of Plato and Aristotle, back in classical Athens during the 4th century BCE. It would spread out in every direction of the compass for the next 2000 years, until it was in many respects erased and whited out by the advent of a new kind of “philosophy,” one belonging peculiarly to the modern West and now exported by all of the processes of Westernization, including the modern Western-style university education. So that it is now a global legacy and liability, like every human inheritance. And an unexamined life is not worth living . . . .

I must admit that by temperament I am a celebrator, although I also hunger for every kind of genuine critique. And as a celebrator it gives me great joy to consider and write about the love of learning and the vitality of each of the focused “roads” (hodoi) of disciplinary investigation in the personal lives and agencies of pre-Cartesian thinkers and educators (and in many since Descartes, in fact). I prefer unfolding the liberating implications of the Greek theory of episteme to polemical protests against the hubris of early-modern philosophy and Enlightenment rationalism, which clearly has very little to do with the brilliant quantitative-experimental methodos Galileo was employing shortly after 1603. How this open-ended investigative methodos could have been confused and conflated with the demonstrative or apodeictic disciplines of mathematics, such as geometria and arithmetike, I can scarecely image, but the new scientia of the Cartesain era did manage to creat an unstable admixture between the investigative disciplines that travel-toward their physical to-be-knowns, in each case, and the relatively few and special disciplines that reason demonstratively from a selected set of arche, their definitions and postulates. Like the Greeks and their successors, I dearly love the purity and exactitude of the mathematic discicplines, and applaud that superb sequent of new mathematical disicplines that emerged in the five dramatic decades between 1650 and 1700: analytical geometry, the calculus, probability and decision theory, and the first of the modern symbolic logics, envisioned by Liebniz as a “universal Caracteristic.” These were all made possible by the new kind of symbolic algebraic reasoning, and by the immense power of the new algebraic equation-mark, and the manipulation of letter-sgns and other component to either side of it, so as to “leave no equation unsolved.”

No, what happened in the 17th century was more fundamental and more catstrophic than the emergence of the scientific method in physics and the splendid new mathematical disciplines. The catstrophe occurred in the field of philosophy proper. It occurred in First Philosophy. And it introduced into the arts & sciences tradition, for the first time in history, a “universal” method. Timeless. Eternal. Indubitable. Absolute. All the philosophical terms I’ve been mentioned changed their meaning and developed strong new senses after 1650. But absolute is perhaps the most telling, because it means absolutely uncontaminated by any temporal processes whatsever — whether historical, linguistic, cultural, or personal-developmental. All these were dismissed as mere “illusions imbibed in chiildhood” (as Descartes called them, and he had been since childhood temperamentally allergic to any field of investigation that had room for a variety of viewpoints). Such as all of the earlier integrative endeavors and centuries-long conversartions that had previously been carried out in the “metaphysical” disciplines of Aristotle: the ones he called first philosophy and theology. Descartes wanted to abolish all of that — and to replace those inquiries into the “highest things and things most divine” with a single, infallible, metaphysical reasoning, from which no mathematically-trained or rational mind could dissent, and for which the world was transformed into “a homogeneous field of objectivity” — inert things and objects made of “matter” and so was suited for a new Cartesain subject, who was made of pure mind. The revolution in philosophy introduced “represenation-thought,” with its theory of language as a system of 1-to-1 equivalences or adequations between objects “in the world” and the concepts “in the mind” that represented each of those objects or states of affairs. What is silently missing from this, the “dominant tradition of [modern] philosophy” (Derrida), is of course time. Lived time, and temporally enacted processes, all of which are vulnerable to the effects of accident and chance — as well as being sustained by causal organizations unfolding themselves in whatever passages of continuous temperality are requisite to each of them for their own manifestations of themselves as themselves. It was upon this dynamic physical world of dynamic unfoldings and upon physical processes manifesting themselves quite powerfully, based on the evidence, but with less than 100% degrees of normative determinacy in each case, that the early Greek-speaking peoples fixed their attention. Theoria is related the “theater,” and the Greek language was highly adapted for thinking ludidly about ongoing organizations or processes dramatically differentiating themselves in that vivid spectacle or panorama of the cosmos in which they saw so much order and beauty, along with inconstancy and fluctuation and random variation.

Each of the Greek disciplines, the Athenians had called a met-hodos — because it was regarded as a “way” (a Greek hodos, or “road”): each pathway being precisely the one “along which” and “by means of which” (meta-) it would be possible for disciplined knowers to travel-toward the truths of their be-knowns, respectively, in each case. Do you happen to remember the “sublime” Parmenides, and his heroic narration concerning the Way of Truth? This was the poem whose epic language first established the philosophical Journey of Knowing at the very core of what constitutes a meaningful human life. For Hypatia or Cicero or Ibn Sina or Aquinas and Dante. Not to mention for the thinkers and artists we know as the Renaissance Christian humanists, among whom Galileo was one . . .

The many distinctive and various Greek “ways” or “pathways” for knowing would be called the via later on, during Latin epochs, and the terms hodoi or methodoi were similarly translated into languages such as Arabic and Persian and Hebrew — everywhere, in fact, where the Athenian vision of a certain bracing education that liberated precisely by means of the irreducible differences between the various modes of investigation, and their to-be-knowns) was welcomed and embraced. Or it wuld be better to say that this was the case during the first 2000 years or so of the Arts & Sciences tradition . . . For, after that, the understandings of philosophy, and of the arts and sciences, changed fundamentally, at least in the West.

When the relaunched website is ready, I will post the link HERE.

At the same time, I will list links there to the major discussions on this earlier weblog, this one you are at, so that you can easily find them, if you wish. And also to the Pages where in 2007 I put some old lectures on the history of literary theory, which emphasized Ferdinand de Saussure and the crucial dynamics of double articulation in language. (Something which the classical Athenian philosophers were fascinated by, and very attentive to. ) These links will be posted HERE soon. Or you can find them in the Archives

Gorgeously haunting Dollhouse music:

Gorgeously haunting Dollhouse music: